I mean, why are we so obsessed with order in the first place? Why do we care whether A happened before B? Why don't we care about some other property, like "color"?

Well, my crazy friend, let's go back to the definition of distributed systems to answer that.

As you may remember, I described distributed programming as the art of solving the same problem that you can solve on a single computer using multiple computers.

This is, in fact, at the core of the obsession with order. Any system that can only do one thing at a time will create a total order of operations. Like people passing through a single door, every operation will have a well-defined predecessor and successor. That's basically the programming model that we've worked very hard to preserve.

The traditional model is: a single program, one process, one memory space running on one CPU. The operating system abstracts away the fact that there might be multiple CPUs and multiple programs, and that the memory on the computer is actually shared among many programs. I'm not saying that threaded programming and event-oriented programming don't exist; it's just that they are special abstractions on top of the "one/one/one" model. Programs are written to be executed in an ordered fashion: you start from the top, and then go down towards the bottom.

Order as a property has received so much attention because the easiest way to define "correctness" is to say "it works like it would on a single machine". And that usually means that a) we run the same operations and b) that we run them in the same order - even if there are multiple machines.

The nice thing about distributed systems that preserve order (as defined for a single system) is that they are generic. You don't need to care about what the operations are, because they will be executed exactly like on a single machine. This is great because you know that you can use the same system no matter what the operations are.

In reality, a distributed program runs on multiple nodes; with multiple CPUs and multiple streams of operations coming in. You can still assign a total order, but it requires either accurate clocks or some form of communication. You could timestamp each operation using a completely accurate clock then use that to figure out the total order. Or you might have some kind of communication system that makes it possible to assign sequential numbers as in a total order.

The natural state in a distributed system is partial order. Neither the network nor independent nodes make any guarantees about relative order; but at each node, you can observe a local order.

A total order is a binary relation that defines an order for every element in some set.

Two distinct elements are comparable when one of them is greater than the other. In a partially ordered set, some pairs of elements are not comparable and hence a partial order doesn't specify the exact order of every item.

Both total order and partial order are transitive and antisymmetric. The following statements hold in both a total order and a partial order for all a, b and c in X:

If a ≤ b and b ≤ a then a = b (antisymmetry); If a ≤ b and b ≤ c then a ≤ c (transitivity);

However, a total order is total:

a ≤ b or b ≤ a (totality) for all a, b in X

while a partial order is only reflexive:

a ≤ a (reflexivity) for all a in X

Note that totality implies reflexivity; so a partial order is a weaker variant of total order. For some elements in a partial order, the totality property does not hold - in other words, some of the elements are not comparable.

Git branches are an example of a partial order. As you probably know, the git revision control system allows you to create multiple branches from a single base branch - e.g. from a master branch. Each branch represents a history of source code changes derived based on a common ancestor:

[ branch A (1,2,0)] [ master (3,0,0) ] [ branch B (1,0,2) ] [ branch A (1,1,0)] [ master (2,0,0) ] [ branch B (1,0,1) ] \ [ master (1,0,0) ] /

The branches A and B were derived from a common ancestor, but there is no definite order between them: they represent different histories and cannot be reduced to a single linear history without additional work (merging). You could, of course, put all the commits in some arbitrary order (say, sorting them first by ancestry and then breaking ties by sorting A before B or B before A) - but that would lose information by forcing a total order where none existed.

In a system consisting of one node, a total order emerges by necessity: instructions are executed and messages are processed in a specific, observable order in a single program. We've come to rely on this total order - it makes executions of programs predictable. This order can be maintained on a distributed system, but at a cost: communication is expensive, and time synchronization is difficult and fragile.

Time is a source of order - it allows us to define the order of operations - which coincidentally also has an interpretation that people can understand (a second, a minute, a day and so on).

In some sense, time is just like any other integer counter. It just happens to be important enough that most computers have a dedicated time sensor, also known as a clock. It's so important that we've figured out how to synthesize an approximation of the same counter using some imperfect physical system (from wax candles to cesium atoms). By "synthesize", I mean that we can approximate the value of the integer counter in physically distant places via some physical property without communicating it directly.

Timestamps really are a shorthand value for representing the state of the world from the start of the universe to the current moment - if something occurred at a particular timestamp, then it was potentially influenced by everything that happened before it. This idea can be generalized into a causal clock that explicitly tracks causes (dependencies) rather than simply assuming that everything that preceded a timestamp was relevant. Of course, the usual assumption is that we should only worry about the state of the specific system rather than the whole world.

Assuming that time progresses at the same rate everywhere - and that is a big assumption which I'll return to in a moment - time and timestamps have several useful interpretations when used in a program. The three interpretations are:

Order. When I say that time is a source of order, what I mean is that:

Interpretation - time as a universally comparable value. The absolute value of a timestamp can be interpreted as a date, which is useful for people. Given a timestamp of when a downtime started from a log file, you can tell that it was last Saturday, when there was a thunderstorm.

Duration - durations measured in time have some relation to the real world. Algorithms generally don't care about the absolute value of a clock or its interpretation as a date, but they might use durations to make some judgment calls. In particular, the amount of time spent waiting can provide clues about whether a system is partitioned or merely experiencing high latency.

By their nature, the components of distributed systems do not behave in a predictable manner. They do not guarantee any specific order, rate of advance, or lack of delay. Each node does have some local order - as execution is (roughly) sequential - but these local orders are independent of each other.

Imposing (or assuming) order is one way to reduce the space of possible executions and possible occurrences. Humans have a hard time reasoning about things when things can happen in any order - there just are too many permutations to consider.

We all have an intuitive concept of time based on our own experience as individuals. Unfortunately, that intuitive notion of time makes it easier to picture total order rather than partial order. It's easier to picture a sequence in which things happen one after another, rather than concurrently. It is easier to reason about a single order of messages than to reason about messages arriving in different orders and with different delays.

However, when implementing distributing systems we want to avoid making strong assumptions about time and order, because the stronger the assumptions, the more fragile a system is to issues with the "time sensor" - or the onboard clock. Furthermore, imposing an order carries a cost. The more temporal nondeterminism that we can tolerate, the more we can take advantage of distributed computation.

There are three common answers to the question "does time progress at the same rate everywhere?". These are:

These correspond roughly to the three timing assumptions that I mentioned in the second chapter: the synchronous system model has a global clock, the partially synchronous model has a local clock, and in the asynchronous system model one cannot use clocks at all. Let's look at these in more detail.

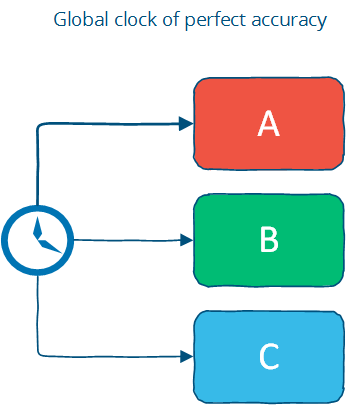

The global clock assumption is that there is a global clock of perfect accuracy, and that everyone has access to that clock. This is the way we tend to think about time, because in human interactions small differences in time don't really matter.

The global clock is basically a source of total order (exact order of every operation on all nodes even if those nodes have never communicated).

However, this is an idealized view of the world: in reality, clock synchronization is only possible to a limited degree of accuracy. This is limited by the lack of accuracy of clocks in commodity computers, by latency if a clock synchronization protocol such as NTP is used and fundamentally by the nature of spacetime.

Assuming that clocks on distributed nodes are perfectly synchronized means assuming that clocks start at the same value and never drift apart. It's a nice assumption because you can use timestamps freely to determine a global total order - bound by clock drift rather than latency - but this is a nontrivial operational challenge and a potential source of anomalies. There are many different scenarios where a simple failure - such as a user accidentally changing the local time on a machine, or an out-of-date machine joining a cluster, or synchronized clocks drifting at slightly different rates and so on that can cause hard-to-trace anomalies.

Nevertheless, there are some real-world systems that make this assumption. Facebook's Cassandra is an example of a system that assumes clocks are synchronized. It uses timestamps to resolve conflicts between writes - the write with the newer timestamp wins. This means that if clocks drift, new data may be ignored or overwritten by old data; again, this is an operational challenge (and from what I've heard, one that people are acutely aware of). Another interesting example is Google's Spanner: the paper describes their TrueTime API, which synchronizes time but also estimates worst-case clock drift.

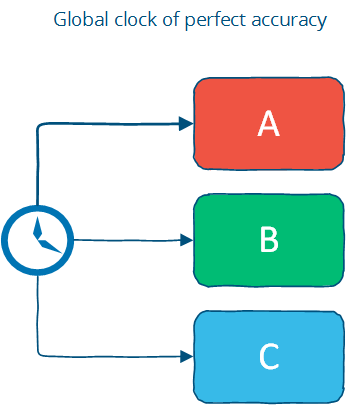

The second, and perhaps more plausible assumption is that each machine has its own clock, but there is no global clock. It means that you cannot use the local clock in order to determine whether a remote timestamp occurred before or after a local timestamp; in other words, you cannot meaningfully compare timestamps from two different machines.

The local clock assumption corresponds more closely to the real world. It assigns a partial order: events on each system are ordered but events cannot be ordered across systems by only using a clock.

However, you can use timestamps to order events on a single machine; and you can use timeouts on a single machine as long as you are careful not to allow the clock to jump around. Of course, on a machine controlled by an end-user this is probably assuming too much: for example, a user might accidentally change their date to a different value while looking up a date using the operating system's date control.

Finally, there is the notion of logical time. Here, we don't use clocks at all and instead track causality in some other way. Remember, a timestamp is simply a shorthand for the state of the world up to that point - so we can use counters and communication to determine whether something happened before, after or concurrently with something else.

This way, we can determine the order of events between different machines, but cannot say anything about intervals and cannot use timeouts (since we assume that there is no "time sensor"). This is a partial order: events can be ordered on a single system using a counter and no communication, but ordering events across systems requires a message exchange.

One of the most cited papers in distributed systems is Lamport's paper on time, clocks and the ordering of events. Vector clocks, a generalization of that concept (which I will cover in more detail), are a way to track causality without using clocks. Cassandra's cousins Riak (Basho) and Voldemort (Linkedin) use vector clocks rather than assuming that nodes have access to a global clock of perfect accuracy. This allows those systems to avoid the clock accuracy issues mentioned earlier.

When clocks are not used, the maximum precision at which events can be ordered across distant machines is bound by communication latency.

What is the benefit of time?

The order of events is important in distributed systems, because many properties of distributed systems are defined in terms of the order of operations/events:

A global clock would allow operations on two different machines to be ordered without the two machines communicating directly. Without a global clock, we need to communicate in order to determine order.

Time can also be used to define boundary conditions for algorithms - specifically, to distinguish between "high latency" and "server or network link is down". This is a very important use case; in most real-world systems timeouts are used to determine whether a remote machine has failed, or whether it is simply experiencing high network latency. Algorithms that make this determination are called failure detectors; and I will discuss them fairly soon.

Earlier, we discussed the different assumptions about the rate of progress of time across a distributed system. Assuming that we cannot achieve accurate clock synchronization - or starting with the goal that our system should not be sensitive to issues with time synchronization, how can we order things?

Lamport clocks and vector clocks are replacements for physical clocks which rely on counters and communication to determine the order of events across a distributed system. These clocks provide a counter that is comparable across different nodes.

A Lamport clock is simple. Each process maintains a counter using the following rules:

Expressed as code:

function LamportClock() < this.value = 1; >LamportClock.prototype.get = function() < return this.value; >LamportClock.prototype.increment = function() < this.value++; >LamportClock.prototype.merge = function(other)A Lamport clock allows counters to be compared across systems, with a caveat: Lamport clocks define a partial order. If timestamp(a) < timestamp(b) :

This is known as clock consistency condition: if one event comes before another, then that event's logical clock comes before the others. If a and b are from the same causal history, e.g. either both timestamp values were produced on the same process; or b is a response to the message sent in a then we know that a happened before b .

Intuitively, this is because a Lamport clock can only carry information about one timeline / history; hence, comparing Lamport timestamps from systems that never communicate with each other may cause concurrent events to appear to be ordered when they are not.

Imagine a system that after an initial period divides into two independent subsystems which never communicate with each other.

However - and this is still a useful property - from the perspective of a single machine, any message sent with ts(a) will receive a response with ts(b) which is > ts(a) .

A vector clock is an extension of Lamport clock, which maintains an array [ t1, t2, . ] of N logical clocks - one per each node. Rather than incrementing a common counter, each node increments its own logical clock in the vector by one on each internal event. Hence the update rules are:

Again, expressed as code:

function VectorClock(value) < // expressed as a hash keyed by node id: e.g. < node1: 1, node2: 3 >this.value = value || <>; > VectorClock.prototype.get = function() < return this.value; >; VectorClock.prototype.increment = function(nodeId) < if(typeof this.value[nodeId] == 'undefined') < this.value[nodeId] = 1; >else < this.value[nodeId]++; >>; VectorClock.prototype.merge = function(other) < var result = <>, last, a = this.value, b = other.value; // This filters out duplicate keys in the hash (Object.keys(a) .concat(b)) .sort() .filter(function(key) < var isDuplicate = (key == last); last = key; return !isDuplicate; >).forEach(function(key) < result[key] = Math.max(a[key] || 0, b[key] || 0); >); this.value = result; >;

This illustration (source) shows a vector clock:

Each of the three nodes (A, B, C) keeps track of the vector clock. As events occur, they are timestamped with the current value of the vector clock. Examining a vector clock such as < A: 2, B: 4, C: 1 >lets us accurately identify the messages that (potentially) influenced that event.

The issue with vector clocks is mainly that they require one entry per node, which means that they can potentially become very large for large systems. A variety of techniques have been applied to reduce the size of vector clocks (either by performing periodic garbage collection, or by reducing accuracy by limiting the size).

We've looked at how order and causality can be tracked without physical clocks. Now, let's look at how time durations can be used for cutoff.

As I stated earlier, the amount of time spent waiting can provide clues about whether a system is partitioned or merely experiencing high latency. In this case, we don't need to assume a global clock of perfect accuracy - it is simply enough that there is a reliable-enough local clock.

Given a program running on one node, how can it tell that a remote node has failed? In the absence of accurate information, we can infer that an unresponsive remote node has failed after some reasonable amount of time has passed.

But what is a "reasonable amount"? This depends on the latency between the local and remote nodes. Rather than explicitly specifying algorithms with specific values (which would inevitably be wrong in some cases), it would be nicer to deal with a suitable abstraction.

A failure detector is a way to abstract away the exact timing assumptions. Failure detectors are implemented using heartbeat messages and timers. Processes exchange heartbeat messages. If a message response is not received before the timeout occurs, then the process suspects the other process.

A failure detector based on a timeout will carry the risk of being either overly aggressive (declaring a node to have failed) or being overly conservative (taking a long time to detect a crash). How accurate do failure detectors need to be for them to be usable?

Chandra et al. (1996) discuss failure detectors in the context of solving consensus - a problem that is particularly relevant since it underlies most replication problems where the replicas need to agree in environments with latency and network partitions.

They characterize failure detectors using two properties, completeness and accuracy:

Strong completeness. Every crashed process is eventually suspected by every correct process. Weak completeness. Every crashed process is eventually suspected by some correct process. Strong accuracy. No correct process is suspected ever. Weak accuracy. Some correct process is never suspected.

Completeness is easier to achieve than accuracy; indeed, all failure detectors of importance achieve it - all you need to do is not to wait forever to suspect someone. Chandra et al. note that a failure detector with weak completeness can be transformed to one with strong completeness (by broadcasting information about suspected processes), allowing us to concentrate on the spectrum of accuracy properties.

Avoiding incorrectly suspecting non-faulty processes is hard unless you are able to assume that there is a hard maximum on the message delay. That assumption can be made in a synchronous system model - and hence failure detectors can be strongly accurate in such a system. Under system models that do not impose hard bounds on message delay, failure detection can at best be eventually accurate.

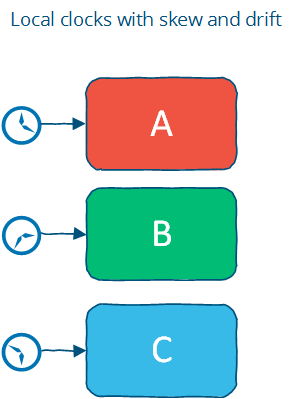

Chandra et al. show that even a very weak failure detector - the eventually weak failure detector ⋄W (eventually weak accuracy + weak completeness) - can be used to solve the consensus problem. The diagram below (from the paper) illustrates the relationship between system models and problem solvability:

As you can see above, certain problems are not solvable without a failure detector in asynchronous systems. This is because without a failure detector (or strong assumptions about time bounds e.g. the synchronous system model), it is not possible to tell whether a remote node has crashed, or is simply experiencing high latency. That distinction is important for any system that aims for single-copy consistency: failed nodes can be ignored because they cannot cause divergence, but partitioned nodes cannot be safely ignored.

How can one implement a failure detector? Conceptually, there isn't much to a simple failure detector, which simply detects failure when a timeout expires. The most interesting part relates to how the judgments are made about whether a remote node has failed.

Ideally, we'd prefer the failure detector to be able to adjust to changing network conditions and to avoid hardcoding timeout values into it. For example, Cassandra uses an accrual failure detector, which is a failure detector that outputs a suspicion level (a value between 0 and 1) rather than a binary "up" or "down" judgment. This allows the application using the failure detector to make its own decisions about the tradeoff between accurate detection and early detection.

Earlier, I alluded to having to pay the cost for order. What did I mean?

If you're writing a distributed system, you presumably own more than one computer. The natural (and realistic) view of the world is a partial order, not a total order. You can transform a partial order into a total order, but this requires communication, waiting and imposes restrictions that limit how many computers can do work at any particular point in time.

All clocks are mere approximations bound by either network latency (logical time) or by physics. Even keeping a simple integer counter in sync across multiple nodes is a challenge.

While time and order are often discussed together, time itself is not such a useful property. Algorithms don't really care about time as much as they care about more abstract properties:

Imposing a total order is possible, but expensive. It requires you to proceed at the common (lowest) speed. Often the easiest way to ensure that events are delivered in some defined order is to nominate a single (bottleneck) node through which all operations are passed.

Is time / order / synchronicity really necessary? It depends. In some use cases, we want each intermediate operation to move the system from one consistent state to another. For example, in many cases we want the responses from a database to represent all of the available information, and we want to avoid dealing with the issues that might occur if the system could return an inconsistent result.

But in other cases, we might not need that much time / order / synchronization. For example, if you are running a long running computation, and don't really care about what the system does until the very end - then you don't really need much synchronization as long as you can guarantee that the answer is correct.

Synchronization is often applied as a blunt tool across all operations, when only a subset of cases actually matter for the final outcome. When is order needed to guarantee correctness? The CALM theorem - which I will discuss in the last chapter - provides one answer.

In other cases, it is acceptable to give an answer that only represents the best known estimate - that is, is based on only a subset of the total information contained in the system. In particular, during a network partition one may need to answer queries with only a part of the system being accessible. In other use cases, the end user cannot really distinguish between a relatively recent answer that can be obtained cheaply and one that is guaranteed to be correct and is expensive to calculate. For example, is the Twitter follower count for some user X, or X+1? Or are movies A, B and C the absolutely best answers for some query? Doing a cheaper, mostly correct "best effort" can be acceptable.

In the next two chapters we'll examine replication for fault-tolerant strongly consistent systems - systems which provide strong guarantees while being increasingly resilient to failures. These systems provide solutions for the first case: when you need to guarantee correctness and are willing to pay for it. Then, we'll discuss systems with weak consistency guarantees, which can remain available in the face of partitions, but that can only give you a "best effort" answer.